“When you say faith is rational, and evidence based … if that were true it wouldn’t be faith would it?

“If there were evidence for it, why would you need to call it faith?” – Richard Dawkins, debating John Lennox, 2007

For many Christians, the notion of “blind faith” is anathema.

Orthodox Christian doctrine holds that through the Bible, God has revealed himself to humanity – culminating in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ in the gospels.

As a result, we have plenty of evidence – or “reason” – with which to justify faith.

The Bible itself attests to this; 1 Peter 3 urges believers to be ready to “make a defence to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you”.

It would appear that, according to the scriptures, faith and reason are perfectly compatible.

However, according to Soren Kierkegaard – the great 19th-century theologian, philosopher, and “father of existentialism” -, there comes a time when reason must take a backseat if we’re to attain “faith”.

Christendom in a golden age

While the “father of existentialism” title is disputed by experts, Soren Kierkegaard is, without doubt, one of the most influential Christian thinkers of the last millennia.

His ideas – captured in 33 books and on over 7000 pages of notes – inspired a new generation of philosophy, with the likes of Satre, Barth, and Bonhoeffer just some of the names to cite him as an influence.

Key to Kierkegaard’s work was rallying against the cultural Christendom of Denmark, and the need for genuine faith to be proved by action.

“Faith is the highest passion in a human being,” he wrote in his seminal 1843 work Fear and Trembling.

“Anyone who comes to faith (whether he be greatly talented or simple-minded makes no difference) won’t remain at a standstill there.”

19th-century Copenhagen, where Soren Kierkegaard lived and worked

Visiting Kierkegaard scholar at Copenhagen University Dr Amber Bowen suggests that Kierkegaard’s core intellectual project was to critique the ‘cultural Christianity’ that had taken hold of Danish society.

“It’s really a context in which the so-called Christian faith is something that was offered comfort and success and position in society,” she said.

“It’s far more convenient for you to be a Christian or claim to be a Christian than to not actually.

“For Kierkegaard, faith was not reducible to content to merely believe or intellectually ascent to. People could agree with the creeds, for example, but that doesn’t mean that they had faith.”

Taking a dancer’s leap

To break out of this Christendom, Kierkegaard saw the need for society to take a “dancer’s leap” to faith.

However, as Amber points out, this has commonly been misunderstood as “jumping” into belief, regardless of any evidence that might suggest otherwise.

“For Kierkegaard, faith is actually more like trust,” she said.

“Trust is not simply cognitive or reducible to cognition, but trust ultimately is this act of giving ourselves fully over to something that maybe we don’t completely understand, but nonetheless, we find so compelling that it is worth everything.

“Faith is legitimized by reason … and a lot of apologies take this approach, I think, in trying to argue for Christianity on these grounds.

“But what, what’s the problem with this? Well, it’s that God can only be what our reason allows him to be.

“So what happens then is we have not actually encountered the truly other, the holy, divine, other, but we’ve only ever constructed a projection of ourselves.”

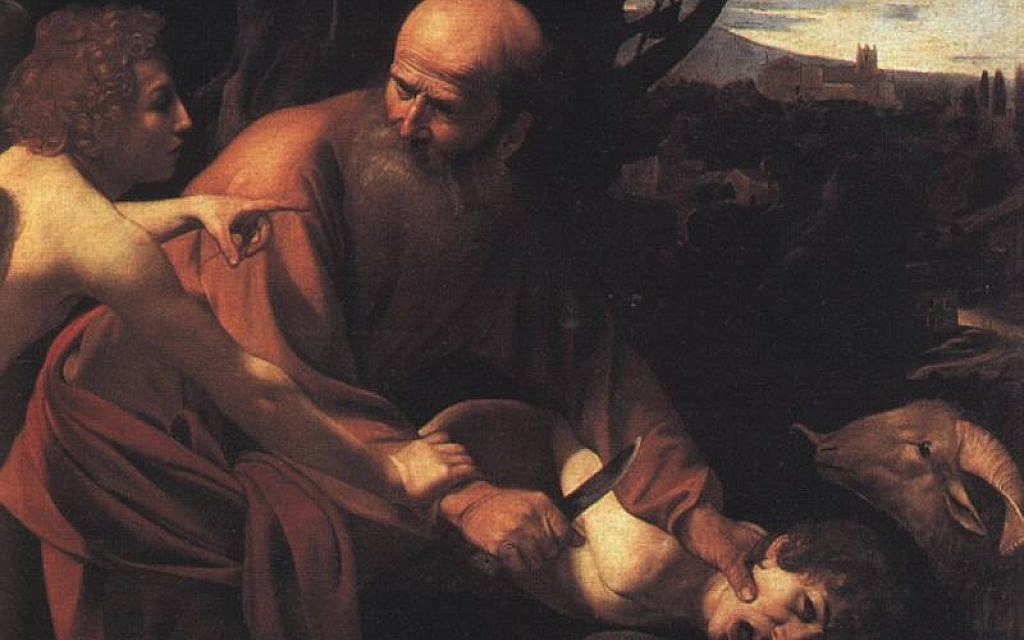

Abraham and Isaac

For Kierkegaard, the ultimate example of this “dancer’s leap” in history is the account of Abraham taking his son Isaac to the top of Mount Moriah to offer as a sacrifice to God – at God’s own command (Genesis 22).

At the moment of sacrifice, an angel of the Lord appears, stopping the grizzly ceremony, and instead offering a lamb, provided by God, for the occasion.

The text reads:

“I swear by myself, declares the Lord, that because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, I will surely bless you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore.

“Your descendants will take possession of the cities of their enemies, and through your offspring, all nations on earth will be blessed, because you have obeyed me.”

For Kierkegaard, this disturbing story was the ultimate marriage of ‘faith and action’.

He writes in Fear and Trembling:

“It is now my intention to draw out from the story of Abraham the dialectical consequences inherent in it, expressing them in the form of problemata, in order to see what a tremendous paradox faith is, a paradox which is capable of transforming a murder into a holy act well-pleasing to God, a paradox which gives Isaac back to Abraham, which no thought can master, because faith begins precisely there where thinking leaves off.”

The story of Abraham and Isaac was, for Kierkegaard, an example of a true “dancer’s leap”

It’s no doubt an unsettling story for most readers, and Kierkegaard’s seemingly mesmerised response may seem bizarre.

However, a closer reading of the story reveals the good nature of God – and proves him worthy of a ‘dancer’s leap’.

“The passage deliberately repeats the word ‘provide’ (yireh), as a reminder that God will provide the sacrifice, not Abraham or Isaac,” said John Dickson.

“In the story, Abraham says to Isaac, ‘God himself will provide [yireh] a lamb for the burnt offering, my son’.

“That’s exactly what ends up happening. And the scene concludes with the words: So Abraham called that place ‘The LORD Will Provide’ [yireh].

“The punchline of the Abraham-Isaac story is, ‘The Lord will provide’ the sacrifice … (and) the punchline of the whole biblical narrative is that God gave himself in sacrifice. That God is worthy of the dancer’s leap!”

“When reason is exalted … you might have a God, but you have the God of the philosophers,” said Amber.

“You have a controllable concept. You don’t have a God that you can fall on your knees in awe of, or dance before.

“Trust ultimately is this act of giving myself fully over to something that maybe I don’t completely understand, but nonetheless, that I find so compelling that it is worth everything.”

Adapted by Alasdair Belling, from ‘Blind Faith‘, an episode of the Undeceptions podcast

Want to be further undeceived?

Check out our network of podcasts and articles in the Undeceptions Library.