By Steve McAlpine (adapted by Alasdair Belling from ‘Balkanisation’ on the Delorean Philosophy podcast)

A DISTURBANCE IN THE FORCE

The United Kingdom had three Prime Ministers in 45 days. The late queen of England Elizabeth the Second reigned for 70 years and welcomed 15 prime ministers into office. She welcomed the last one, a woman also called Elizabeth, just two days before she died, aged 96. 44 days later the new Prime Minister is an ex-Prime Minister, forced to resign due to a disastrous economic plan.

Two Elizabeths in power – then gone in quick succession.

Queen Elizabeth welcomed her first Prime Minister in 1952 – sir Winston Churchill. Churchill was born in 1875 during the reign of Queen Victoria.

Queen Victoria was proclaimed empress of India in 1877, a move by parliament to bind India even closer to the British Empire. Britain’s current Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, has been welcomed into office by the new King, Charles the Third.

Rishi Sunak is 42. His Hindu parents migrated from east Africa in the 1960s. He will be the first non-caucasian Prime Minister of the UK. The monarchy that once ruled India now welcomes a Prime Minister who is ethnically Indian. A lot can happen in 150 years … 45 days for that matter.

Let’s not laugh at their dilemma regarding political churn – the rest of us aren’t doing much better.

In 1983 my family had just returned to Australia from living in the UK. I was in high school and a new prime minister – Bob Hawke – was sworn into office.

In 2007 – some 24 years later – I once again returned to Australia from the UK. This time I was married, I had a daughter and a child on the way, but between 1983 and 2007 we’d had 24 only three prime ministers in Australia. We just assumed a leader took office and stayed and stayed. How wrong we were!

In the fifteen years since 2007, the prime ministership in Australia has changed no less than seven times, down from an eight-year average to a smidgeon more than two.

In the United States of America? Four-year terms for the presidency have not stopped the churn of politics. Congress and the Senate are in turmoil, still reeling from the January sixth protests outside the homes of supreme court justices, which saw both red and blue sides carrying signs reading “not my president”.

Many self-identifying Democrats say that they don’t have Republican friends and vice-versa. Not because they don’t know any but because they don’t want to know any.

Increasingly, the language we use to describe those on the other side of the political fence is not attributed to intellectual capacity, but moral culpability. Opponents are not wrong, they are bad. Ideas are not unworkable but are evil. We distrust politics and despise politicians. We promote one person or party only to tear them down when they don’t perform how we want them to. and the gap between promoting and tearing down is growing shorter and shorter.

SO WHERE’S IT ALL GOING?

It doesn’t sound like it’s going in a good direction, and it’s all being played out against a backdrop of two bellicose leaders in Russia and China, both one-party states.

Clearly, our political churn in the west is a sign of a deeper cultural churn. Conservative commentator Andrew Breitbart once made the memorable statement “politics is downstream of culture”. You don’t have to be a conservative to realise it’s true. If the politics is churning, look at what is happening culturally that is driving this churn.

In one sense Breitbart was only seeing things from a conservative position: the stories we tell ourselves and the stories that are told to us shape us far more than anything else does.

Culture is an elusive word – but whatever I read from the left or the right of politics – conservative or progressive – it rings true that our cultural stories are churning, and hence so too are our politics. Who are we? Who gets to decide? What does it mean to flourish as a human? What does it even mean to be a human?

Once, when it came to answering those questions we were all singing from roughly the same hymn sheet.

I’m using the term “hymn sheet” deliberately. Even if we were not Christian in the West there was a wide ecumenism that tacitly admitted we all shared roughly a common goal for society and roughly an equal idea of what human flourishing and human morality looked like. The story that Christianity gave us was the pole star. Some of us were closer to it, others not so close. Some heading towards it, some away. But it was there nonetheless.

Now? That is no longer true. The pole star is fading and with it the gravity that propels or repels us. In her interesting new book ‘Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World’, Vox Magazine’s religion editor Tara Isabella Burton maps the religious fracturing of the West and the rise of what she calls the “religious remixed”. Contrary to what the rationalists and humanists were hoping we’re just as superstitious and religiously oriented as ever. It just hits different.

Burton is not simply interested in what a religion “is”. There are bullet points that could answer that. She’s more interested in what a religion “does”. In short, she focuses on meaning, purpose, community and ritual as the framework. Burton says this fourfold search is impossible to kill off. observing that the decline in institutional religion has coincided with the internet age (causation or correlation – we can argue that another day).

At the same time, there is a rise in the desire to “self-craft” religion. We have the technology to meet our desires, and we own the platform to cobble “bespoke” religious identities that often don’t look religious but fulfil religion’s quadrant functions. Institutions are letting us down best to stick with intuition – so the narrative goes.

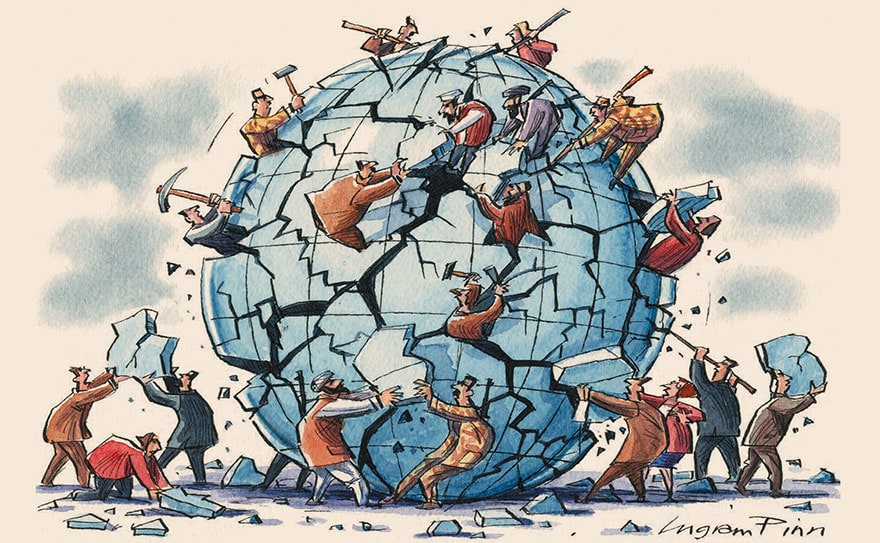

But it’s not just religious institutions falling short of the mark – political ones have crumbled too. It’s a fracturing age, splintering into a kaleidoscope of colour and identity.

Burton notes that “the refractory nature of these new intuitional religions – each one at its core a religion of the self – risks creating an increasingly balkanised American culture, one in which our desire for personal authenticity and experiential fulfilment takes precedence over our willingness to build coherent ideological systems and functional, sustainable institutions. When we are all our own high priests who are willing to kneel?”

I love that quote! Perhaps it means this: if religiously we are all priests then politically we are all Presidents or Prime Ministers, fracturing and refracting, longing for intuitional politics as much as we long for intuitional religions.

Burton says the rise of the self-focussed wellness culture in the West is linked to this intuitional drive. The failure of the political system to predict and then deal with Donald Trump led to a deepening dismay and distrust of institutions. She observes: “if our trusted sources of authority couldn’t predict Trump’s election, why shouldn’t we fall back on more immediate sources of authority: our feelings, our wants, our physical needs?”

It turns out “you do you” is a necessity, not a luxury! But let’s revisit that term she used of where we and the west are at; ‘Balkanised’.

The Balkans is a region in south-central Europe, generally agreed to consist of former Yugoslavian nations Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia.

Balkanisation technically means the division of a multinational state into smaller, ethnically homogeneous groups. However, in the bloody aftermath of the war that fractured Yugoslavia in the 1990s, it’s taken on a more menacing idea. The ethnic division led to ethnic conflict, which led to the as-yet-unfinished war crimes trials in the Hague.

The West is Balkanising. We are fracturing not along ethnic lines as much as cultural lines. If we are all our own high priests and no one is willing to kneel, and we are all our own Prime Ministers and Presidents but no one is willing to cede, how do we get other people to do what we want them to do?

There’s only one way; power.

Everything will be reduced to a power struggle. No one thinks the worst effects of Balkanisation could happen to them. But one of the bywords from the horror stories of Balkanisation is Sarajevo.

Sarajevo was a strategic city in Bosnia, one of those ethnic micro-states within the fracturing Yugoslavia. It is famous – or perhaps infamous – for experiencing the longest city siege in modern warfare. 1425 days of horror, death and bombardment. That is what Sarajevo became known for.

But it wasn’t always the case. Sarajevo hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics, at a time when it was in its prime, economically and culturally. Yet by the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Sarajevo was atop the podium for all the wrong reasons – a gold medalist in the Balkanisation stakes. Granted, it has survived and is now indeed thriving – but what a journey. It’s easy to look at eastern Europe and think that can’t happen to us. But Balkanisation doesn’t begin with political fracturing – it begins with cultural fracturing and seeing “the other” as not only wrong but evil. Depersonalising one’s opponent and making them “the enemy”.

Perhaps we seem a long way from that. Opposition MPs on both sides of the UK parliament expressed outrage at the murders of Labour MP Jo Cox, and Conservative MP sir David Amess in recent years. However, the sci-fi movie Children of Men offers a warning.

In it, the UK is balkanised. Life is cheap, the country is split into warring tribes, and bombs explode in London cafes. It seems so outrageous, so impossible – and yet, as with all good near-future sci-fi, it’s just within the realms of possibility.

If culture is upstream of politics, and cultural Balkanisation is a thing, then politics downstream has some heavy lifting to do to ensure we don’t get there.

SO WHAT CAN WE DO ABOUT THIS?

Nadija Mujagic was a teenager during the siege of Sarajevo. In her first memoir of the war ‘Ten Thousand Shells and Counting’ she recalls life before Balkanisation.

“The neighbourhood felt like a family, and like every family, there were dysfunctions and disagreements, but everyone knew you could count on each other. Being a Muslim, a Croat, or a Serb was never a source of contention; rather, being a bad neighbour was.”

Surely the Western world is nowhere near as divided as Muslims, Croats and Serbs were back then. What kept them together? What stopped the divide and churn? It wasn’t conformity, was it?

There’s zealotry in the west today that demands purity. No dysfunctions, no disagreements, but suffocating conformity – and it’s arrived at exactly the same time that we are fracturing culturally. Nadija’s observation was that the main concern in Sarajevo was not which ethnic grouping you belonged to, but whether you were a good neighbour or not. It’s interesting that Jesus had stuff about neighbourliness, and what made a good one. The story of the good Samaritan is a case in point for Croats – it’s the story of the good Serb or for Serbs – the story of the good Muslim or in my case – from northern Ireland – the story of the good Catholic.

Jesus isn’t naïve – he acknowledges that we have enemies as well as neighbours. How are we to respond to our enemies? We love them and do good to those who persecute us because that’s what Jesus did. Central to our intuitional religion is the idea that we – and we alone – are ok … and perhaps those who agree with us. Our selfishness is somehow warranted, and our rejection of others is simply our way of getting rid of negativity in our lives. Those who disagree with us or are – in our terms – dysfunctional, and are enemies worth despising.

Never before have we had so many opportunities for conflict while having so few tools to deal with it. It’s Balkanisation all the way down. The beauty of Children of Men is its final scene. The premise of the story is that women across the globe have stopped giving birth, and without children, wombs are empty, schools are empty, playgrounds are barren and hearts are destitute. However, in the bloodbath of the ensuing fighting, a child is born. As that child is carried out of a shrapnel-shredded building soldiers lower their guns, wonder crosses their faces and tenderness fills their hearts. Hope for the future is rekindled. The children of men stop focusing on themselves and see their desperate need for something outside themselves to bring them back together.

The book of Ephesians in the Bible says of Jesus Christ that he himself is our peace. Jesus is the man who halts the dreaded Balkanisation overtaking us. He stops the churn, he brings warring parties together and he does the ultimate good for his cultural, political and spiritual enemies by dying for them.

If the political churn we have been experiencing in the west is a sign of a deeper existential churn that is building within our culture, then Jesus is someone worth kneeling before.

Want to be further undeceived?

Check out our network of podcasts and articles in the Undeceptions Library.