An undergrad student starting at Oxford 600 years ago would have had an unrecognisable timetable in comparison to a student today.

All pupils – boys and girls, rich and poor – would learn 7 disciplines: the first three, known as the trivium, were grammar, logic, and rhetoric (all designed so you could think and communicate thoughts).

The next four, or quadrivium, were more about interrogating reality: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. Together, these formed the so-called ‘liberal arts’ – and this was the foundation of all education until really recently!

Only after this foundational education would a student then begin to specialise in a discipline such as the law, theology, or medicine.

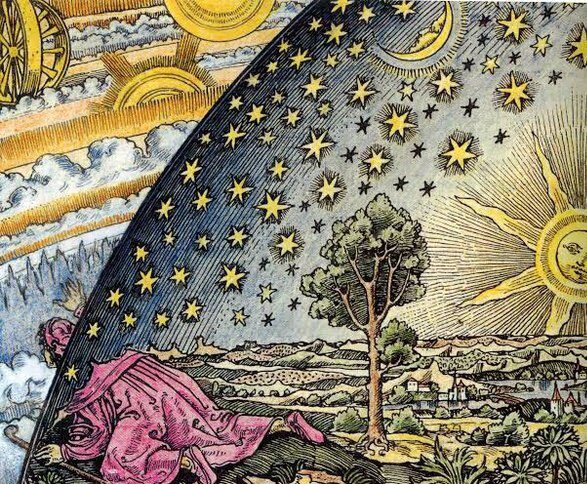

The quadrivium depicted (clockwise from top left) – arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music

A Unified World

Underpinning this type of education was the sense that all branches of knowledge were somehow mysteriously connected.

It was a world ruled by an intellectual tradition called “natural philosophy”.

According to Emeritus Professor and Oxford hero Alister McGrath, natural philosophy went beyond the “what” of science, and delved into the “why”?

“What are our responsibilities towards nature? What can we learn from it? What can we learn about it? It’s really this total way of engaging the natural world and becoming better people as a result. That’s natural philosophy,” he said.

Although (like many things) natural philosophy could trace its roots back to ancient Greece and the work of Plato and Aristotle, it was really the medieval world that saw it flourish.

Of course, religion had a big role to play in this, as many academics believed understanding the world around them gave insight to their god.

Many of the foremost natural philosophers of the Middle Ages were theists – be they Christian, Jewish, or Islamic.

“There’s an Islamic natural philosophy (particularly in Spain) There’s a Jewish natural philosophy, and they’re all doing the same thing, but interestingly, bringing their own specific theological commitments to it,” said McGrath.

“Natural Philosophy is a broad church, and certainly those who were agnostic or atheist would have had a seat at the table without any particular difficulty.”

Some of the most famous names in intellectual history fell squarely into the natural philosopher category.

Undeceptions favourites the Venerable Bede and Thomas Aquinas both undertook natural philosophy as part of their work, as did later intellectuals including Da Vinci, Newton, and even Einstein.

The latter famously wrote that:

“So many people today—and even professional scientists—seem to me like somebody who has seen thousands of trees but has never seen a forest.

“A knowledge of the historical and philosophical background gives that kind of independence …. (which)—in my opinion— is the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker of truth.”

The world of natural philosophy also saw great strides taken in intra-faith cooperation.

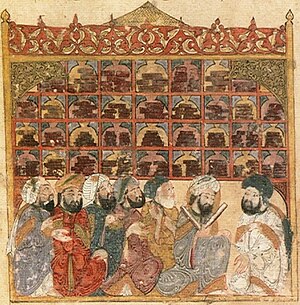

In 9th-century Baghdad, the “House of Wisdom” was a community of Christian scholars working side by side with their Islamic colleagues, studying the classical Greek traditions of mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy, especially Aristotle.

Islamic scholars then made huge strides in all these areas, before taking that knowledge, including Aristotle, back into the far West in Spain. And from there – almost doing a geographical and intellectual circle – this knowledge came back into Western Europe.

A 13th-century artwork depicting scholars gathered at the House of Wisdom

Elsewhere, Jewish natural philosopher Moses Maimonides (also called Rambam) wrote on Jewish law and the Bible, astronomy, and Philosophy in the 12th century. His book Guide for the Perplexed was an attempt to reconcile Hebrew-Jewish traditions with Greek philosophy and rational observation.

Natural Philosophy eventually gave way to the fragmentation of science and philosophy proper following the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

From that came the likes of chemistry, biology, physics, and so on, with scientists narrowing their focus to specific fields of study.

McGrath though thinks the tradition of natural philosophy can – and should – still influence the modern academy.

“The first thing we lose is any sense that nature is special or that nature in some way,” McGrath said.

“If you look at something like (late American Physicist) Steven Weinberg’s attempt to give a history of natural sciences, it’s very much a functional approach to nature, and Weinberg’s very clear, we have to leave behind these outdated ideas of science engaging with meaning or value. It’s simply trying to work out how things function. We have lost something there in a big way.”

McGrath also fears that without the spirit of natural philosophy, cross-disciplinary work will suffer.

He’s based this on his own observations having spent plenty of time on the inside.

“I think science nowadays is seen rather as a technocratic discipline where in effect you have people who research and crunch numbers, but if you want to know the meaning of life, you’re not going to ask them,” he said.

“So in effect, we have a disengagement of what would once have been seen as one of the most important areas of reflection on this topic with the big questions of meaning and value.

“I think is very important (because) we need to try and bridge the gaps between professional disciplines.

“I’m finding in my conversations here at Oxford that people are wonderfully informed about their own disciplines, but don’t really get to others, and don’t know how to talk or make connections with others.

“(Natural Philosophy) positions yourself within this bigger picture of reality, and realize you have responsibilities, you have privileges, and you can exalt in the beauty of this world.”

Adapted by Alasdair Belling from the Undeceptions episode ‘True Science’. Listen to here

Want to be further undeceived?

Check out our network of podcasts and articles in the Undeceptions Library.