When Sarah first arrived at Cambridge on a scholarship, and then later took a job at Oxford, she thought Christians were anti-intellectual. And perhaps that’s what we’ve come to expect. Smart people have no time – no headspace – for God. They know too much. They think too deeply for the ‘shallows’ of theology.

This episode, we’re talking with people who’ve witnessed the opposite. Universities like Oxford and Cambridge are melting pots, where people can find their beliefs – or unbelief – turned upside down, just like Sarah.

Links related to this episode:

- Read more of Sarah’s conversion to Christianity during her studies here.

- Check out Vaughan Robert’s ministry at St Ebbe’s in Oxford University.

- Read Peter Harrison’s The Fall of Man and the Foundations of Science

- Find out more about philosopher Peter Singer

- John Dickson’s 5 minute Jesus in this episode is all about Christianity and the Apostles’ Creed. Learn more about the creed here.

- Read more about CS Lewis’ conversion to Christianity while at Oxford

- Get GK Chesterton’s book The Everlasting Man

- More on Oxford University banning the Christian Union at Fresher’s Week in 2017

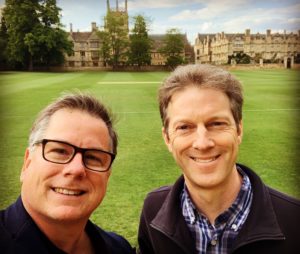

John and Vaughan Roberts walking around Oxford.

Thanks to our season sponsor – Selah – for all your travel needs, whether you’re a doubter or a believer. Find out more at myselah.com.au.

Get to know our guests

Vaughan Roberts is Rector of St Ebbe’s Church in Oxford. He studied law at Cambridge University and theology at Wycliffe Hall in Oxford before entering ministry. Roberts is also Director of the Proclamation Trust, an organisation that encourages and equips Bible teachers. He is a popular conference speaker and author of several books.